A fiscal year is a 12-month accounting period that businesses and organizations use to track income, expenses, and financial performance—but unlike the standard calendar year that runs from January 1 to December 31, a fiscal year can begin and end in any month. This flexibility allows companies to align their financial reporting with natural business cycles, industry trends, or seasonal patterns. For tax purposes, understanding the difference between a fiscal year and a calendar year is essential, as it affects filing deadlines, strategic planning, and compliance with IRS regulations. Whether you’re a small business owner, corporate accountant, or curious taxpayer, knowing how these two timeframes function can help you make smarter financial decisions.

What Is a Fiscal Year?

A fiscal year is a 12-month period used by businesses, governments, and nonprofit organizations for accounting, budgeting, and financial reporting. Unlike the calendar year, which always starts on January 1 and ends on December 31, a fiscal year can begin in any month and end 12 months later. This flexibility allows organizations to choose a financial cycle that better reflects their operational patterns. For example, many retailers opt for a fiscal year that ends in January to capture the entire holiday shopping season in a single reporting period, while educational institutions often use a July-to-June fiscal year to match the academic calendar. The chosen fiscal year is typically labeled by the calendar year in which it ends—for instance, a fiscal year ending on March 31, 2026, would be called FY 2026.

Calendar Year vs. Fiscal Year: Key Differences

While both a calendar year and a fiscal year span 12 consecutive months, the key difference lies in their start and end dates. A calendar year always runs from January 1 to December 31 and is commonly used by individuals and many small businesses for its simplicity and alignment with personal tax deadlines. In contrast, a fiscal year can begin in any month and is often selected by businesses to better reflect their financial activities, seasonal income patterns, or industry practices. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for tax filing, financial planning, and regulatory compliance.

Here’s a comparison of the two:

| Feature | Calendar Year | Fiscal Year |

| Timeframe | January 1 – December 31 | Any 12-month period not starting in January |

| Common Users | Individuals, small businesses | Corporations, seasonal or industry-specific |

| IRS Default | Yes | Requires IRS approval for change |

| Reporting Simplicity | High | Moderate to complex |

| Alignment with Operations | May not align | Can match business cycles |

| Tax Filing Deadline | April 15 (typically) | Varies by fiscal year-end |

| Year-End Financial Clarity | Straightforward | Often provides clearer seasonal reporting |

Why Some Businesses Choose a Fiscal Year

Not all businesses operate on a steady, year-round schedule. For companies with seasonal fluctuations or unique operational cycles, sticking to the traditional January-to-December calendar year might not reflect their true financial performance. That’s why many organizations choose a fiscal year that aligns more closely with their busiest periods, sales peaks, or industry-specific needs. Selecting a fiscal year can enhance financial clarity, improve planning accuracy, and provide strategic tax advantages.

Here are some common reasons businesses opt for a fiscal year:

1. Alignment with Business Cycles: Companies can match their reporting periods with when they earn the most revenue or incur significant expenses.

2. Clearer Seasonal Reporting: Businesses that rely heavily on seasonal sales—like retail or agriculture—can include entire busy seasons within one fiscal period.

3. Easier Budgeting and Forecasting: Financial planning becomes more effective when aligned with actual operational flows rather than the calendar year.

4. Tax Strategy Optimization: Choosing a fiscal year can help defer income, accelerate deductions, or align tax payments with cash flow cycles.

5. Avoiding Peak Audit Season: Some businesses select non-calendar fiscal years to ease the workload on accountants and reduce audit and filing costs.

6. Industry Norms: Certain sectors—like education or government—often follow specific fiscal years based on institutional or policy standards.

IRS Rules and Tax Filing Requirements

IRS Rules and Tax Filing Requirements

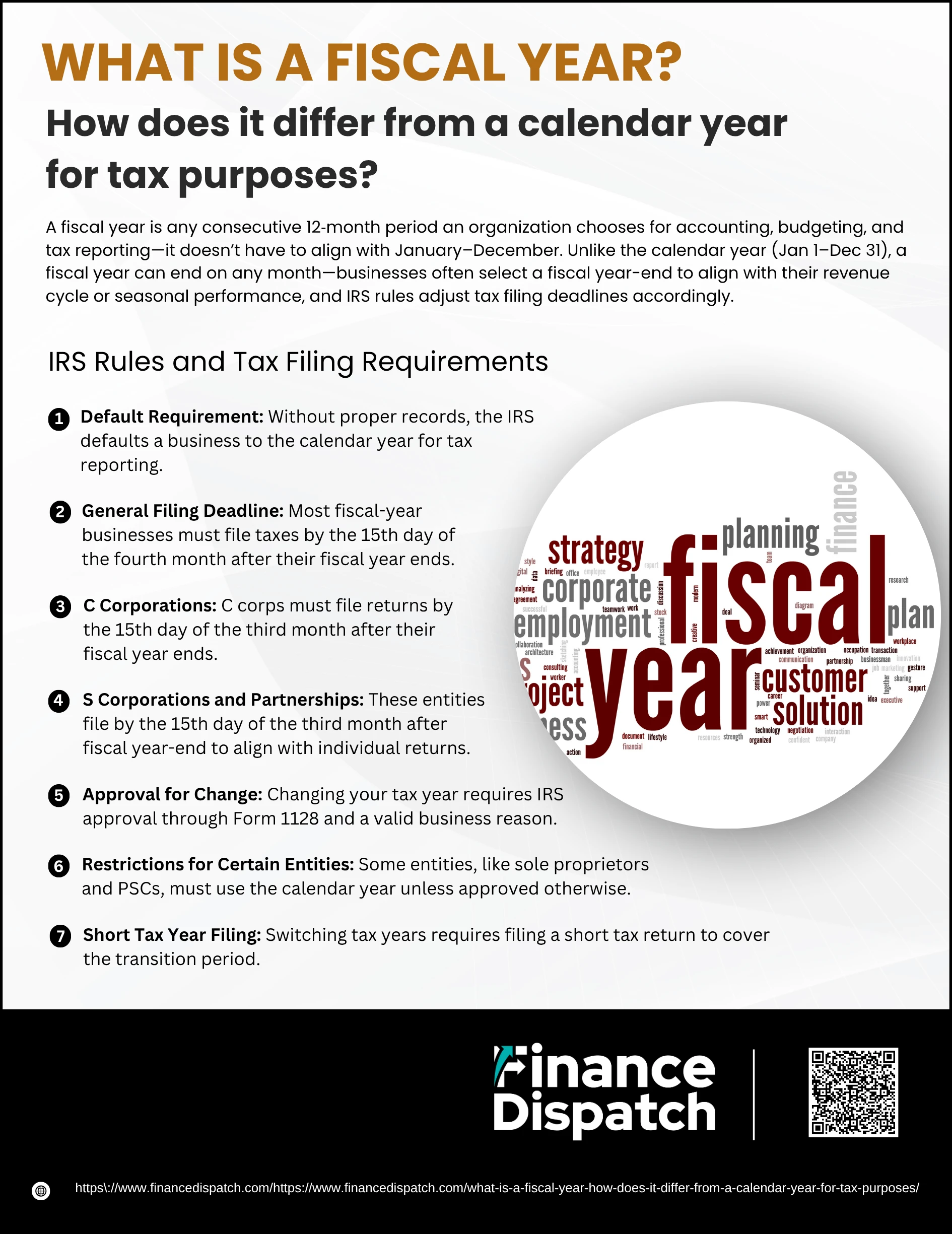

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) allows businesses to choose between using a calendar year or a fiscal year for tax reporting, but certain rules and deadlines must be followed. While the calendar year is the default for most taxpayers, businesses that opt for a fiscal year must comply with specific IRS guidelines, including adjusted filing dates and potential approval requirements. Failing to adhere to these rules can lead to penalties, missed deadlines, or invalid tax returns.

Here are key IRS rules and tax filing requirements for fiscal year filers:

1. Default Requirement

If a business fails to establish a formal accounting system or maintain adequate financial records, the IRS automatically assigns a calendar year for tax purposes. This means the business must report income from January 1 to December 31, regardless of how its internal operations are structured. This rule ensures consistency and prevents companies from manipulating tax timing due to vague reporting.

2. General Filing Deadline

For most businesses using a fiscal year, the IRS requires annual tax returns to be submitted by the 15th day of the fourth month following the end of the fiscal year. For example, a business whose fiscal year ends on June 30 must file its return by October 15. This adjusted deadline ensures businesses have time to close their books and prepare accurate filings based on their chosen fiscal timeline.

3. C Corporations

C corporations have a slightly different deadline—they must file their tax returns by the 15th day of the third month after the end of their fiscal year. So, if a C corporation’s fiscal year ends on March 31, it must file by June 15. This shorter timeline reflects the nature of corporate tax structures and ensures timely payment of taxes owed.

4. S Corporations and Partnerships

These entities are also required to file their tax returns by the 15th day of the third month after their fiscal year ends, regardless of the specific fiscal dates chosen. Since S corporations and partnerships are pass-through entities (income is passed to shareholders or partners), this earlier deadline allows individual recipients to meet their personal filing deadlines.

5. Approval for Change

Switching from a calendar year to a fiscal year (or vice versa) isn’t a casual decision—it requires IRS approval via Form 1128: Application to Adopt, Change, or Retain a Tax Year. Businesses must provide a solid reason—such as aligning with a parent company, adjusting for seasonal revenues, or matching industry norms. Without approval, changing your tax year can result in rejected filings or penalties.

6. Restrictions for Certain Entities

Some business types, especially sole proprietors and Personal Service Corporations (PSCs)—such as those in law, health, or accounting—are generally required to use the calendar year. These restrictions exist to prevent potential tax avoidance by manipulating fiscal periods. However, exceptions may be granted if a legitimate business purpose can be demonstrated and IRS approval is secured.

7. Short Tax Year Filing

When a business transitions from one tax year to another—say, from a calendar year to a fiscal year—it must file a short tax year return. This covers the period between the old year-end and the new fiscal year start. For instance, if a business switches its year-end from December to June, it would file a short tax return covering January through June. This ensures there are no gaps in tax reporting and all income is accounted for during the transition.

Tax Planning Opportunities with a Fiscal Year

Tax Planning Opportunities with a Fiscal Year

Choosing a fiscal year instead of a traditional calendar year can open up strategic tax planning opportunities for businesses. By aligning financial reporting with operational peaks and cash flow cycles, companies can better manage when income is recognized and when expenses are incurred. This flexibility can lead to deferred tax liabilities, optimized deductions, and more accurate financial forecasting—all of which are crucial for effective tax strategy and financial health.

Here are several ways a fiscal year can benefit tax planning:

1. Income Deferral

Businesses can postpone recognizing revenue until the next tax year by ending their fiscal year before peak income periods. For example, a construction company might choose a fiscal year ending March 31, allowing it to delay recognizing summer revenue until the following tax cycle.

2. Expense Timing

Companies can schedule significant purchases or investments at the end of their fiscal year to maximize deductions in the current tax period. This tactic is particularly useful for businesses with cyclical cash flow, such as those in retail or agriculture.

3. Tax-Loss Harvesting

Aligning a fiscal year with the business cycle enables companies to strategically recognize losses—such as inventory write-downs or asset disposals—at times that most effectively offset taxable income from profitable periods.

4. Improved Cash Flow Management

With a customized fiscal year, businesses can time tax payments in line with high-revenue months, ensuring they have the liquidity needed to meet obligations without financial strain.

5. Avoidance of Tax Season Bottlenecks

Ending a fiscal year outside of traditional calendar year-end allows businesses to file taxes when accountants and auditors are less busy, potentially reducing professional fees and expediting the filing process.

Examples of Fiscal Year Structures by Sector

Different industries operate on varying business cycles, and many choose fiscal year structures that best align with their peak activity periods. By tailoring the fiscal year to reflect operational and seasonal patterns, businesses can present more accurate financial reports and make better-informed decisions. Here are some common fiscal year structures used across different sectors:

1. U.S. Federal Government: October 1 to September 30, designed to accommodate budget planning and align with legislative sessions.

2. Retail Industry (e.g., Walmart): Ends on January 31 to include the full holiday shopping season and post-holiday returns in a single financial period.

3. Technology Sector (e.g., Apple Inc.): Ends in September to capture back-to-school sales and pre-holiday product launches.

4. Educational Institutions: Typically July 1 to June 30, aligning with the academic year and tuition cycles.

5. Nonprofit Organizations: Often mirror academic or grant cycles—July 1 to June 30 or October 1 to September 30—depending on funding schedules.

7. Agricultural Businesses: May use a fiscal year ending after harvest season (e.g., September 30) to better reflect income from crop sales.

8. Hospitality and Tourism: Often end their fiscal year after the peak tourist season (e.g., March 31) to account for seasonal revenue accurately.

9. Healthcare Organizations: Frequently use fiscal years aligned with government funding or insurance reimbursement schedules, such as October 1 to September 30.

Choosing or Changing Your Fiscal Year

Selecting the right fiscal year is a critical decision that can impact how your business manages taxes, cash flow, and financial reporting. For new businesses, the choice is often made when filing the first tax return. For established companies, changing an existing fiscal year requires approval from the IRS and careful planning. Whether you’re choosing your fiscal year for the first time or considering a switch, understanding the requirements and consequences is essential to staying compliant and maximizing financial efficiency.

Here are key considerations when choosing or changing your fiscal year:

1. Align with Business Cycles: Select a fiscal year that ends after your peak business season to capture full-cycle revenues and expenses.

2. IRS Approval Required: Existing businesses must file IRS Form 1128 to request approval for changing their fiscal year.

3. Short Tax Year Transition: A change in fiscal year will create a short tax year, requiring special handling of financial statements and tax filings.

4. Entity Restrictions Apply: Sole proprietors and S corporations usually must follow the calendar year unless they demonstrate a valid business reason and receive IRS approval.

5. Update Internal Systems: Changing your fiscal year means updating accounting software, budgeting timelines, and reporting schedules to reflect the new structure.

6. Notify Stakeholders: Inform investors, lenders, auditors, and employees about the change to ensure alignment across financial operations.

7. Consider Industry Norms: Aligning with fiscal year practices common in your industry can simplify benchmarking and investor communication.

Conclusion

Choosing between a fiscal year and a calendar year is more than a matter of preference—it’s a strategic decision that can influence your business’s financial clarity, tax obligations, and operational efficiency. While the calendar year offers simplicity and aligns with most individual tax filings, a well-chosen fiscal year can better reflect your business cycle, provide meaningful tax planning opportunities, and streamline financial reporting. Whether you’re launching a new venture or reassessing your current structure, aligning your fiscal year with your organization’s unique needs can lead to more accurate insights, better compliance, and improved decision-making.