Have you ever wondered why a small drop in the price of your favorite snack makes you rush to the store, while a rise in fuel prices barely changes your driving habits? This difference in consumer behavior is captured by a concept economists call price elasticity of demand. It’s a powerful tool that measures how much the quantity demanded of a product changes when its price goes up or down. Understanding this elasticity not only helps businesses set smarter prices but also reveals just how sensitive—or indifferent—consumers are to price changes. In this article, we’ll explore what price elasticity of demand really means, how it’s calculated, the factors that influence it, and most importantly, how it reflects consumer responsiveness in the real world.

What is Price Elasticity of Demand?

Price elasticity of demand is an economic concept that measures how sensitive consumers are to changes in the price of a product or service. In simple terms, it tells us how much the quantity demanded will increase or decreases when the price rises or falls. If a small change in price leads to a significant change in demand, the product is considered to have elastic demand. On the other hand, if demand barely changes despite a price shift, it is inelastic. This measurement helps businesses and policymakers understand consumer behavior and make informed decisions about pricing, production, and taxation.

How Does Price Elasticity of Demand Measure Consumer Responsiveness?

How Does Price Elasticity of Demand Measure Consumer Responsiveness?

Price elasticity of demand serves as a numerical indicator of how responsive consumers are to price changes. By comparing the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in price, it quantifies the strength of a consumer’s reaction. For example, if a small increase in price causes a large drop in sales, it shows that consumers are highly responsive, indicating elastic demand. Conversely, if demand remains nearly the same despite price fluctuations, consumers are less responsive, showing inelastic demand. This measurement helps businesses predict how their customers might react to price adjustments, enabling them to craft pricing strategies that align with market behavior and maximize revenue.

How to Calculate Price Elasticity of Demand

Calculating price elasticity of demand (PED) helps you understand how much the quantity demanded of a product changes in response to a change in its price. This calculation is a valuable tool for businesses looking to set effective pricing strategies, manage revenue, and anticipate customer behavior. By using a simple formula, you can measure whether your product is elastic or inelastic.

Here’s how to calculate it:

- Step 1: Identify the original and new prices of the product.

This helps determine the percentage change in price. - Step 2: Identify the original and new quantities demanded.

This shows how consumer demand has shifted. - Step 3: Calculate the percentage change in price.

(NewPrice–OriginalPrice)÷OriginalPrice×100(New Price – Original Price) ÷ Original Price × 100(NewPrice–OriginalPrice)÷OriginalPrice×100 - Step 4: Calculate the percentage change in quantity demanded.

(NewQuantity–OriginalQuantity)÷OriginalQuantity×100(New Quantity – Original Quantity) ÷ Original Quantity × 100(NewQuantity–OriginalQuantity)÷OriginalQuantity×100 - Step 5: Use the PED formula.

PriceElasticityofDemand=Price Elasticity of Demand = % Change in Quantity Demanded ÷ % Change in PricePriceElasticityofDemand = - Step 6: Interpret the result.

- Greater than 1 = Elastic demand (high consumer responsiveness)

- Less than 1 = Inelastic demand (low consumer responsiveness)

- Equal to 1 = Unitary elasticity (proportional response)

Types of Price Elasticity of Demand

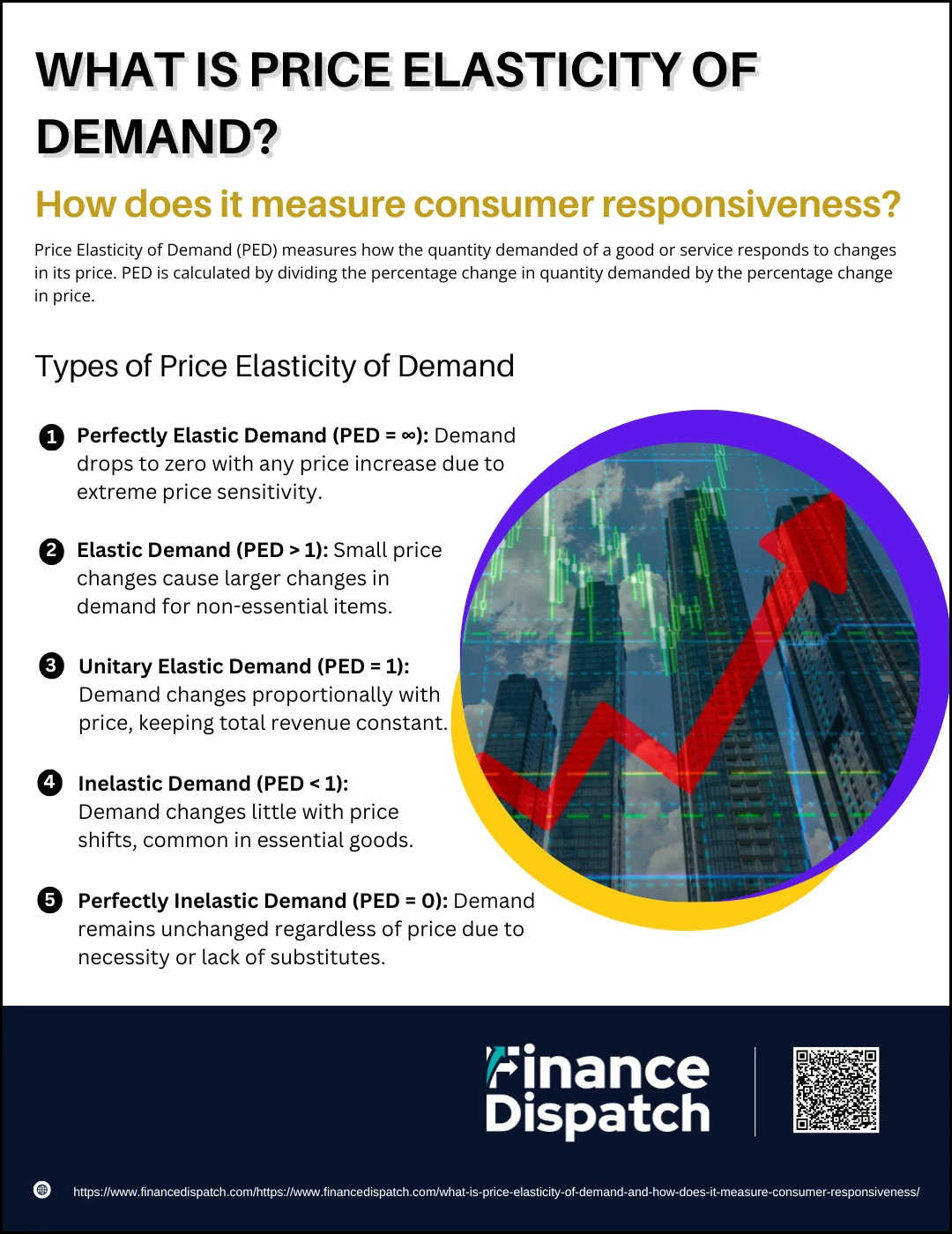

Price elasticity of demand (PED) reveals how the quantity demanded of a product responds to changes in its price. While the general concept helps us understand consumer behavior, categorizing the types of elasticity provides deeper insights into how different products react to pricing shifts. Let’s explore each type in more detail:

1. Perfectly Elastic Demand (PED = ∞)

In this rare and mostly theoretical case, even the slightest increase in price causes the quantity demanded to drop to zero. Consumers are extremely price-sensitive and will not tolerate any variation. They’ll immediately switch to alternatives if the price goes up, and the seller has no pricing power. This scenario is often used to illustrate a perfectly competitive market where identical products are sold, and buyers can get the same item elsewhere without any hassle.

2. Elastic Demand (PED > 1)

When a product has elastic demand, it means consumers are very responsive to price changes. A 1% decrease in price leads to a greater than 1% increase in quantity demanded. This usually applies to goods that are not necessities and have many substitutes—like branded clothing, electronics, or restaurant dining. Businesses selling elastic products must be cautious with price increases, as even small hikes can significantly reduce demand.

3. Unitary Elastic Demand (PED = 1)

In this situation, the percentage change in quantity demanded equals the percentage change in price. For instance, a 10% price increase leads to a 10% decrease in demand. This balance means total revenue remains unchanged, regardless of the price movement. Products with unitary elasticity are at a tipping point where price adjustments neither benefit nor harm revenue significantly.

4. Inelastic Demand (PED < 1)

Inelastic demand refers to goods where consumers are not highly responsive to price changes. A 10% increase in price might only cause a 2% drop in quantity demanded. These products are typically necessities—such as gasoline, milk, or electricity—where consumers continue buying despite higher costs because they need them for daily living. Companies with inelastic products often have more pricing flexibility.

5. Perfectly Inelastic Demand (PED = 0)

This is the other extreme, where demand does not change at all regardless of price movements. Even if the price doubles or triples, consumers will still buy the same amount. This type of demand is typically associated with life-saving or essential items like insulin for diabetics or oxygen tanks for patients. Because of the total lack of substitutes and critical nature of the product, demand is completely insensitive to price.

Factors Affecting Price Elasticity of Demand

Factors Affecting Price Elasticity of Demand

Price elasticity of demand (PED) doesn’t exist in a vacuum—several real-world factors influence whether a product’s demand is elastic or inelastic. These factors help explain why consumers may react strongly to price changes for one product but barely respond to changes in another. Understanding these influences allows businesses to predict how price shifts might affect sales and revenue. Here are the key factors that affect price elasticity of demand:

1. Availability of Substitutes

The more substitutes available for a product, the more elastic its demand tends to be. If consumers can easily switch to another brand or similar product when prices rise, they’re more likely to change their buying behavior. For example, if the price of one soft drink rises, consumers may easily switch to another similar brand.

2. Necessity vs. Luxury

Necessities such as basic food items, electricity, and medications have inelastic demand because people need them regardless of price. Luxury goods, on the other hand, are more elastic since they are not essential, and consumers can postpone or avoid buying them when prices rise.

3. Proportion of Income Spent on the Product

If a product consumes a large portion of a consumer’s income, its demand tends to be more elastic. For instance, a 10% price increase in cars or furniture may lead to a substantial drop in demand. In contrast, goods that cost a small fraction of income—like toothpaste or salt—tend to be inelastic.

4. Time Period Considered

Elasticity often increases over time. In the short run, consumers may not adjust their habits immediately. But over the long run, they might find alternatives or change their behavior. For example, if gasoline prices rise, people may continue buying in the short term but might eventually switch to public transport or fuel-efficient cars.

5. Brand Loyalty

Strong customer loyalty can make demand more inelastic. Consumers who are loyal to a specific brand may continue purchasing it even if the price rises. This is common in markets where brand identity, trust, and perceived quality outweigh cost concerns—such as with smartphones or designer apparel.

6. Addictiveness or Habitual Use

Products like cigarettes, coffee, or alcohol tend to have inelastic demand because they are habit-forming or addictive. Even with significant price increases, consumers may not reduce consumption drastically, as these products are tied to physical or psychological needs.

7. Definition of the Product

The broader the product category, the more inelastic the demand. For example, demand for “food” in general is inelastic, but demand for specific types of food, like premium ice cream, is more elastic because substitutes exist within the broader category.

Real-World Examples of Elastic and Inelastic Demand

Price elasticity of demand plays out clearly in everyday life. Depending on the nature of the product, some goods show significant changes in demand when prices change, while others barely move. These real-world examples help illustrate how elastic or inelastic demand affects consumer behavior, business pricing strategies, and market outcomes. Below are some common examples of both elastic and inelastic demand:

Examples of Elastic Demand

1. Airline Tickets

When ticket prices rise, many travelers postpone trips or look for cheaper alternatives, making air travel highly sensitive to price.

2. Restaurant Meals

Dining out is often a discretionary expense, so consumers tend to cut back or choose lower-cost options when prices go up.

3. Electronics (e.g., Smartphones, Laptops)

With many models and brands available, consumers can easily switch if one becomes too expensive.

4. Fashion Apparel

Clothing that isn’t essential tends to have elastic demand—especially luxury or branded fashion items.

5. Streaming Subscriptions

Price hikes in monthly entertainment services may lead users to cancel or switch providers due to abundant alternatives.

Examples of Inelastic Demand

1. Gasoline

Despite rising prices, many people continue to buy gas out of necessity for commuting or business use.

2. Prescription Drugs

Medications, especially life-saving ones, often have no close substitutes, leading to very inelastic demand.

3. Basic Groceries (e.g., Milk, Bread)

These staple food items are needed for daily life, so demand remains relatively stable despite price fluctuations.

4. Utilities (Water, Electricity)

Essential for daily living, these services typically see little change in usage even with increased pricing.

5. Addictive Goods (e.g., Cigarettes, Alcohol)

Even with higher taxes or price hikes, demand often remains steady due to physical or psychological dependence.

Why Price Elasticity Matters for Business and Policy

Price elasticity of demand isn’t just a theoretical concept—it has practical implications that directly affect how businesses operate and how governments make economic decisions. By understanding how sensitive consumers are to price changes, companies can set better prices to maximize revenue, while policymakers can design taxes and subsidies that achieve social and economic goals. Here’s why price elasticity matters so much in the real world:

For Businesses

1. Optimizing Pricing Strategies

Knowing if a product is elastic or inelastic helps businesses set prices that either boost sales volume or increase revenue with minimal demand loss.

2. Forecasting Revenue Changes

Price elasticity allows businesses to predict how changes in pricing might impact total sales and profitability.

3. Managing Product Portfolios

Firms can decide which products to promote or phase out based on their elasticity, prioritizing those with stable demand.

4. Adapting to Market Trends

Businesses can monitor changes in elasticity over time to stay responsive to shifts in consumer preferences or competitive dynamics.

For Policymakers

1. Designing Effective Tax Policies

Governments often place higher taxes on inelastic goods (like tobacco or fuel) to raise revenue without drastically reducing consumption.

2. Allocating Subsidies Wisely

Understanding elasticity helps target subsidies toward elastic goods where price reductions can significantly improve access and affordability.

3. Predicting Public Reaction to Price Controls

When setting price caps or floors, policymakers use elasticity to gauge how consumers and producers might respond.

4. Evaluating Economic Impact

Elasticity data aids in analyzing the potential economic outcomes of policy changes, such as shifts in minimum wage or import tariffs.

Limitations of Price Elasticity of Demand

Limitations of Price Elasticity of Demand

Price elasticity of demand (PED) offers valuable insights into how consumers respond to price changes, but it’s not a perfect measure. In the real world, human behavior, market complexity, and changing economic conditions introduce limitations that can reduce the accuracy or usefulness of PED. Relying solely on elasticity figures without understanding their constraints can lead to flawed business or policy decisions. Below are the major limitations of PED explained in greater detail:

1. Assumes Other Factors Are Constant (Ceteris Paribus)

PED calculations are based on the assumption that only the price of the good changes while all other influencing factors—such as consumer income, tastes, competitor prices, and advertising—stay constant. However, in actual markets, multiple variables often shift at the same time, making it hard to isolate the effect of price alone.

2. Difficult to Measure Accurately

Accurately calculating PED requires precise data on price changes and corresponding demand responses. This data can be inconsistent or unavailable, especially for smaller businesses. Seasonal trends, regional preferences, and customer segments may further distort measurements, making results unreliable or non-generalizable.

3. Ignores Consumer Psychology and Behavior

PED focuses on quantifiable changes but doesn’t account for psychological factors that heavily influence consumer decisions. For example, a loyal customer may continue to buy a favorite brand despite a price increase, or consumers may perceive a higher-priced product as better quality, increasing its appeal. These nuances are beyond the scope of elasticity calculations.

4. Short-Term vs. Long-Term Elasticity

Elasticity values can vary depending on the time frame considered. In the short term, consumers may continue buying a product out of habit or necessity, making it appear inelastic. Over time, however, they might find substitutes, adjust their budgets, or change consumption habits, making demand more elastic. Failing to consider this distinction can lead to incorrect conclusions.

5. Not Equally Applicable to All Products or Markets

For new products, luxury items, or highly differentiated goods, reliable data may not exist to calculate PED. Moreover, some goods behave differently depending on customer demographics or locations, making elasticity values too context-specific to apply universally.

6. Doesn’t Reflect Market Structure or Competition

PED assumes a basic competitive environment but doesn’t factor in the broader market structure. For example, in a monopoly, even highly elastic products may be priced without fear of losing customers due to lack of alternatives. Similarly, aggressive promotions or pricing tactics by competitors can shift demand in ways not predicted by elasticity alone.

Conclusion

Price elasticity of demand is a powerful concept that helps explain how consumers respond to price changes, offering valuable insights for businesses, economists, and policymakers alike. It allows us to quantify consumer sensitivity and make strategic decisions around pricing, product planning, taxation, and subsidies. However, while PED provides a useful framework, it’s important to recognize its limitations—such as the assumption of constant variables, difficulty in accurate measurement, and the exclusion of consumer psychology. By combining elasticity insights with real-world market analysis and behavioral understanding, decision-makers can craft smarter strategies that align with consumer needs and market realities.