When it comes to taxing what we buy, most people are familiar with the concept of sales tax—an amount added at the register when you purchase goods or services. But in many parts of the world, a different system is used: the Value-Added Tax (VAT). Though both VAT and sales tax are forms of consumption tax collected by sellers and remitted to the government, they operate in fundamentally different ways. Understanding how VAT works, how it compares to sales tax, and why it matters can help consumers, businesses, and policymakers make more informed financial decisions in a global economy.

What Is Value-Added Tax (VAT)?

Value-Added Tax (VAT) is a type of consumption tax applied incrementally at each stage of a product’s supply chain—from production to the final sale. Unlike sales tax, which is charged only at the point of sale to the end consumer, VAT is collected throughout the manufacturing and distribution process whenever value is added. Each business involved charges VAT on its sales and can deduct the VAT it has paid on its purchases, remitting only the difference to the government. Ultimately, the final cost of VAT is borne by the consumer, making it a widely used yet often misunderstood form of indirect taxation.

History and Global Use of VAT

The concept of Value-Added Tax (VAT) originated in Europe and was first implemented in France in 1954 by tax official Maurice Lauré. Although earlier ideas of taxing value addition had been proposed in Germany, France became the pioneer in adopting VAT as a comprehensive taxation model. Since then, VAT has spread globally and is now used by more than 170 countries, including all members of the European Union and most industrialized nations within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Despite its widespread adoption, the United States remains a notable exception, relying instead on a sales tax system. Globally, VAT has become a vital source of government revenue, offering a more consistent and structured way to tax consumption across different sectors.

How VAT Works

How VAT Works

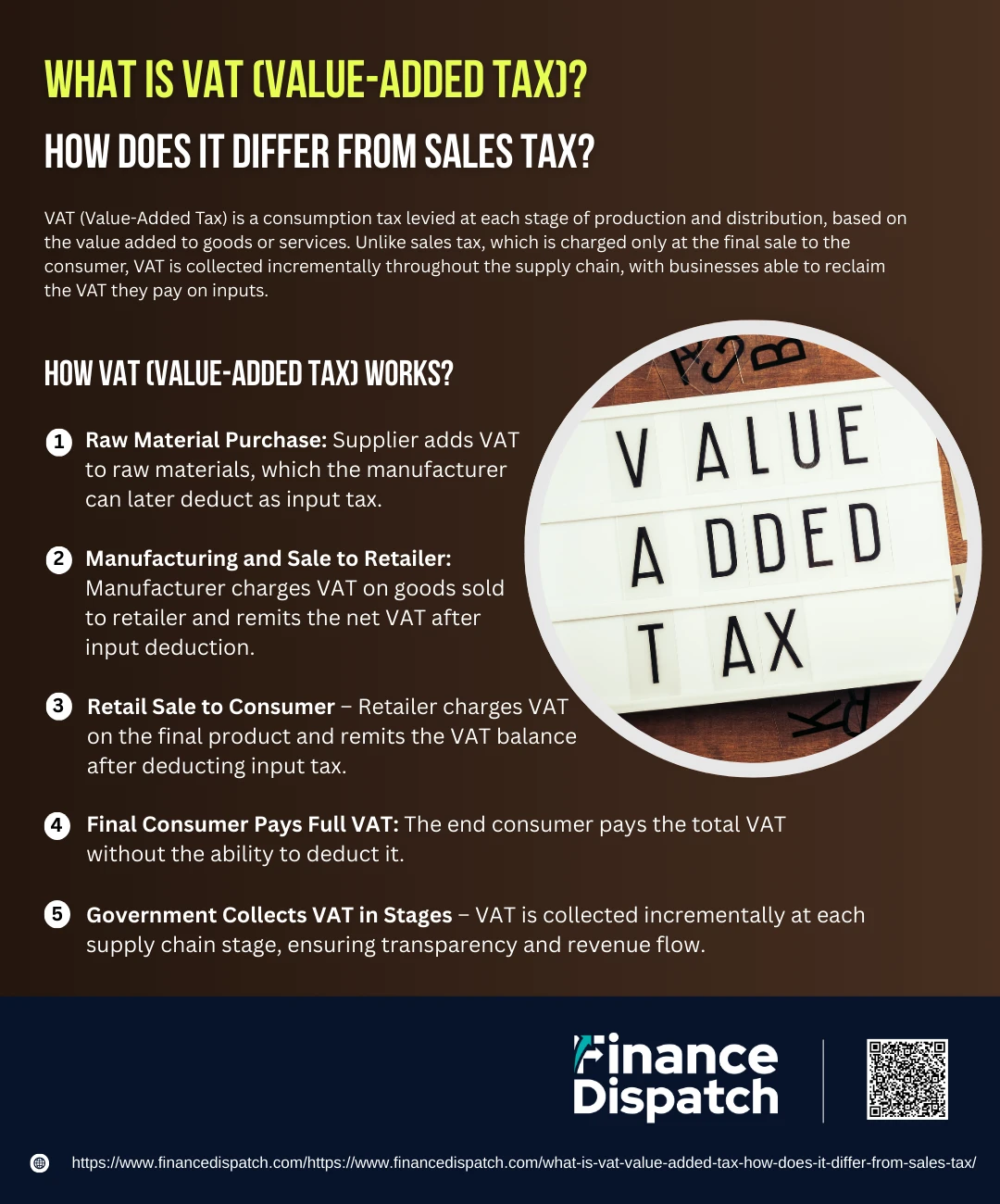

Value-Added Tax (VAT) is a multi-stage consumption tax levied on the value added to goods and services at every point in the supply chain. Unlike sales tax—which is imposed only at the final sale to the consumer—VAT is collected and remitted at each stage of production and distribution. Businesses charge VAT on their sales (output tax) and can deduct the VAT they paid on purchases (input tax), ultimately passing the full tax burden to the end consumer. Here’s a closer look at how this process unfolds:

1. Raw Material Purchase

The supply chain begins when a manufacturer purchases raw materials—for example, wood and metal—from a supplier at a cost of $100. The supplier adds 10% VAT, totaling $110. The $10 VAT is collected by the supplier and remitted to the government. This $10 becomes the manufacturer’s input tax, which can later be deducted.

2. Manufacturing and Sale to Retailer

The manufacturer uses the raw materials to produce goods and sells them to a retailer for $200. The manufacturer charges a 10% VAT on the sale, adding $20 to the invoice. However, the manufacturer has already paid $10 in VAT on the raw materials. Therefore, the manufacturer remits only the difference—$10—to the government ($20 output VAT – $10 input VAT).

3. Retail Sale to Consumer

The retailer now sells the finished product to the end consumer for $300. The 10% VAT on this sale amounts to $30. The retailer must remit $10 to the government after deducting the $20 VAT it paid to the manufacturer. This continues the chain of tax collection and deduction.

4. Final Consumer Pays Full VAT

The final consumer pays the full $300 price, which includes the $30 VAT. Unlike businesses in the supply chain, consumers cannot deduct the VAT paid. This is where the tax burden settles—on the end user.

5. Government Collects VAT in Stages

At each stage of the supply chain, the government collects VAT in increments: $10 from the supplier, $10 from the manufacturer, and $10 from the retailer. This method enhances transparency, reduces the risk of tax evasion, and provides a steady stream of revenue throughout the production process.

Advantages and Disadvantages of VAT

Advantages and Disadvantages of VAT

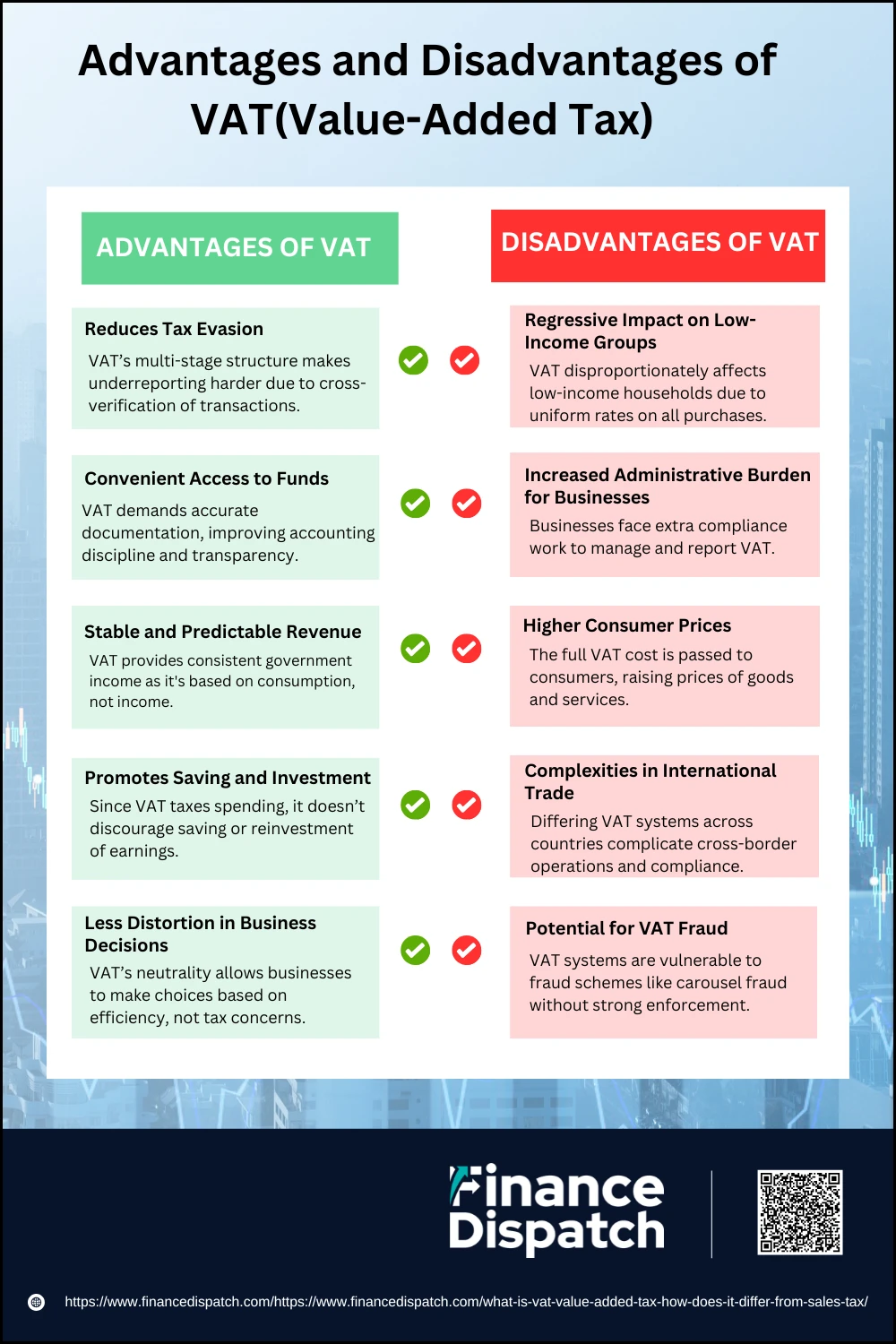

Value-Added Tax (VAT) is a widely adopted consumption-based tax system used in more than 170 countries. Its appeal lies in the way it spreads tax collection across the supply chain, creating multiple points of revenue and reducing opportunities for tax evasion. However, while VAT may streamline tax collection for governments, it presents challenges for businesses and may impact lower-income consumers more heavily. Below is a closer look at the major advantages and disadvantages of VAT:

Advantages of VAT

1. Reduces Tax Evasion

VAT is collected at every stage of production and distribution, which means each business involved must report its transactions. This built-in system of checks—where one company’s purchase is another’s sale—makes it more difficult to underreport income or sales, unlike income tax systems that rely solely on individual reporting.

2. Encourages Better Record-Keeping

To claim VAT deductions on business purchases, companies must keep precise and verifiable records of transactions. This requirement promotes disciplined accounting and makes audits easier and more reliable, improving overall financial transparency.

3. Stable and Predictable Revenue

Unlike income tax, which fluctuates based on profits or employment levels, VAT is linked to spending. People continue to purchase goods and services even during economic downturns, ensuring that governments receive a relatively steady revenue stream year-round.

4. Promotes Saving and Investment

Because VAT taxes consumption, not earnings, it doesn’t penalize individuals or businesses for saving or reinvesting profits. In theory, this can lead to increased national savings and more productive investments in the economy.

5. Less Distortion in Business Decisions

Since VAT is neutral in its structure—taxes are applied uniformly and input VAT is reclaimable—it avoids interfering with business choices about pricing, sourcing, and production. Companies can operate based on efficiency rather than tax planning.

Disadvantages of VAT

1. Regressive Impact on Low-Income Groups

VAT applies the same rate to everyone, regardless of income. This means that lower-income households, which spend a higher portion of their earnings on basic goods, end up paying a higher percentage of their income in tax compared to wealthier households—making VAT inherently regressive.

2. Increased Administrative Burden for Businesses

Implementing VAT requires businesses to manage additional paperwork, track input and output taxes meticulously, and comply with strict filing deadlines. For small or new businesses, the cost and complexity of compliance can be a significant barrier.

3. Higher Consumer Prices

Since businesses typically pass the VAT burden down the supply chain, the final consumer bears the full weight of the tax. This leads to higher prices for goods and services, especially where VAT rates are high or exemptions are limited.

4. Complexities in International Trade

Different countries have varying VAT rates, exemption rules, and refund procedures. Businesses operating across borders must navigate this complexity, which can increase compliance costs and risk of errors or penalties.

5. Potential for VAT Fraud

Despite its transparency, VAT systems can still be exploited through fraudulent schemes. One common example is carousel fraud, where companies repeatedly reclaim VAT on phantom transactions involving non-existent exports. If enforcement is weak, such practices can lead to significant revenue loss.

What Is Sales Tax?

Sales tax is a type of indirect tax imposed by governments on the sale of goods and certain services, typically at the point of final retail purchase. Unlike VAT, which is collected at each stage of the supply chain, sales tax is charged only once—when the end consumer buys the product. The seller is responsible for collecting the tax from the buyer and remitting it to the appropriate tax authority. In the United States, sales tax is not governed federally but is administered at the state and local levels, leading to wide variations in rates and rules across jurisdictions. Some goods, such as groceries or prescription medications, may be exempt depending on the region. Sales tax is considered a consumption tax because it applies to spending rather than income, and like VAT, the financial burden ultimately falls on the consumer.

VAT vs. Sales Tax: Key Differences

Although both VAT (Value-Added Tax) and sales tax are forms of consumption tax, they differ significantly in how they are applied, collected, and managed. While VAT is charged at every stage of production and allows businesses to reclaim taxes paid on inputs, sales tax is levied only once—at the final point of sale to the consumer. These differences impact everything from pricing and tax compliance to international trade and revenue collection. The following table outlines the key distinctions between the two systems:

| Aspect | Value-Added Tax (VAT) | Sales Tax |

| Tax Collection Point | At every stage of the supply chain | Only at the final retail sale to the end consumer |

| Who Pays the Tax | All businesses in the chain (with credit for input VAT) | Only the final consumer |

| Who Remits the Tax | Every registered seller along the chain | Only the retailer |

| Tax Recovery | Businesses can reclaim input VAT on purchases | No recovery mechanism for tax paid on purchases |

| Invoice Requirements | Detailed invoices with VAT numbers are mandatory | Invoices typically show tax separately, less detail required |

| Price Transparency | Often tax-inclusive (depending on country) | Usually added at checkout |

| Risk of Tax Evasion | Lower due to cross-verification between input and output tax | Higher due to single-point collection |

| Administrative Complexity | Higher due to multi-stage reporting and record-keeping | Lower, but varies by state/local rules |

| Prevalence | Used in over 170 countries worldwide | Common in the U.S., but not used federally |

| Impact on Prices | Can increase final prices but spread over stages | Tax is added only at the end, clearly visible to the buyer |

Examples Comparing VAT and Sales Tax

To better understand how VAT and sales tax function in real-world scenarios, it’s helpful to compare them side by side using a simple example. Imagine a basic supply chain involving a farmer, a baker, and a retailer. Both VAT and sales tax ultimately result in the same amount of tax collected, but the timing and method of collection differ significantly. Here’s how the two systems compare in a typical transaction:

1. Under a VAT System (Assuming 10% VAT):

- A farmer sells wheat to a baker for $0.30 + $0.03 VAT. The farmer remits $0.03 to the government.

- The baker uses the wheat to bake bread and sells it to a retailer for $0.70 + $0.07 VAT. The baker deducts $0.03 (input VAT) and remits $0.04.

- The retailer sells the bread to a consumer for $1.00 + $0.10 VAT. The retailer deducts $0.07 and remits $0.03 to the government.

- Total tax paid by consumer: $0.10

- Total VAT collected in stages: $0.03 (farmer) + $0.04 (baker) + $0.03 (retailer)

2. Under a Sales Tax System (Assuming 10% Sales Tax):

- No tax is applied when the farmer sells wheat to the baker.

- No tax is applied when the baker sells bread to the retailer.

- The retailer sells the bread to a consumer for $1.00 + $0.10 sales tax, and remits the entire $0.10 to the government.

- Total tax paid by consumer: $0.10

- Tax collected in one stage only: $0.10 (retailer)

Impact of VAT on the U.S. Economy

The implementation of a Value-Added Tax (VAT) in the United States has been a topic of extensive debate among economists and policymakers. Proponents argue that a federal VAT could generate substantial revenue—potentially between $250 billion and $500 billion annually—providing a reliable source of funding for essential government services and reducing the federal deficit. Unlike income tax, which fluctuates with earnings, VAT is based on consumption, offering more consistent revenue even during economic downturns. However, critics highlight the potential downsides, including increased consumer prices, the risk of job losses in certain sectors, and the disproportionate burden on lower-income households. Studies have also warned that introducing VAT could disrupt current state and local tax systems, requiring significant coordination and reform. While VAT may offer economic advantages in terms of efficiency and revenue stability, its broader impact on consumption, employment, and social equity remains a key concern in the U.S. context.

Who Gains and Who Loses from VAT?

The effects of VAT are not distributed equally across all income groups, leading to clear winners and losers. Wealthier consumers tend to benefit more under a VAT system, especially if it replaces income taxes, because they save a larger portion of their income and spend relatively less on taxed necessities. As a flat consumption tax, VAT does not increase with income, so high earners pay the same rate as those with lower incomes—making the system regressive. In contrast, lower-income households, which spend most of their income on essential goods and services, end up paying a larger share of their earnings in VAT. Businesses may also face increased administrative burdens, though they benefit from input tax deductions and clearer tax structures. Overall, while VAT is efficient for governments, it may amplify economic inequality unless mitigated through targeted exemptions, lower rates on essentials, or support programs for vulnerable groups.

VAT Refunds for Travelers

Travelers who make purchases in countries that charge Value-Added Tax (VAT) may be eligible for a VAT refund on certain items bought during their visit. These refunds typically apply to goods like clothing, jewelry, electronics, or souvenirs that are taken out of the country, while services such as hotel stays, food, and entertainment are usually excluded. To claim a refund, travelers must request VAT-specific receipts at the time of purchase and complete refund forms—often at the airport or departure point—before leaving the country. Some refund systems offer immediate cash back, while others process the refund later via mail or bank transfer, usually deducting a small service fee. Although the process requires careful documentation and can vary by country, VAT refunds can offer meaningful savings, making it a worthwhile option for tourists who shop abroad.

Conclusion

Value-Added Tax (VAT) and sales tax are both consumption-based systems designed to generate government revenue, but they differ significantly in structure and impact. VAT is collected in stages throughout the supply chain and is widely adopted across the globe, while sales tax is typically imposed only at the final point of sale, as seen in the United States. Each system has its strengths and weaknesses—VAT offers better compliance and stable revenue but can be regressive, while sales tax is simpler but more prone to evasion. Understanding these differences is essential for consumers, businesses, and policymakers, especially as discussions continue about tax reform and the potential role of VAT in the U.S. economy.