Taxes are a fundamental tool governments use to fund public services, but not all taxes are created—or applied—the same way. One of the most important distinctions lies between consumption taxes and income taxes. While income taxes are levied when you earn money, consumption taxes are charged when you spend it. This article explores what a consumption tax is, how it functions in everyday transactions, and how it compares to income tax in terms of fairness, efficiency, and economic impact. Understanding this difference can help you make smarter financial decisions and recognize how tax systems shape spending and saving behaviors.

What Is a Consumption Tax?

A consumption tax is a tax imposed on the purchase of goods and services, meaning you pay it when you spend money rather than when you earn it. Unlike income tax, which targets wages, salaries, and investment returns, consumption tax applies at the point of sale and is usually included in the price you pay as a consumer. This tax can take several forms—such as sales tax, value-added tax (VAT), excise duties, or import tariffs—and is typically collected by the seller, who then remits it to the government. Essentially, the more you consume, the more tax you pay.

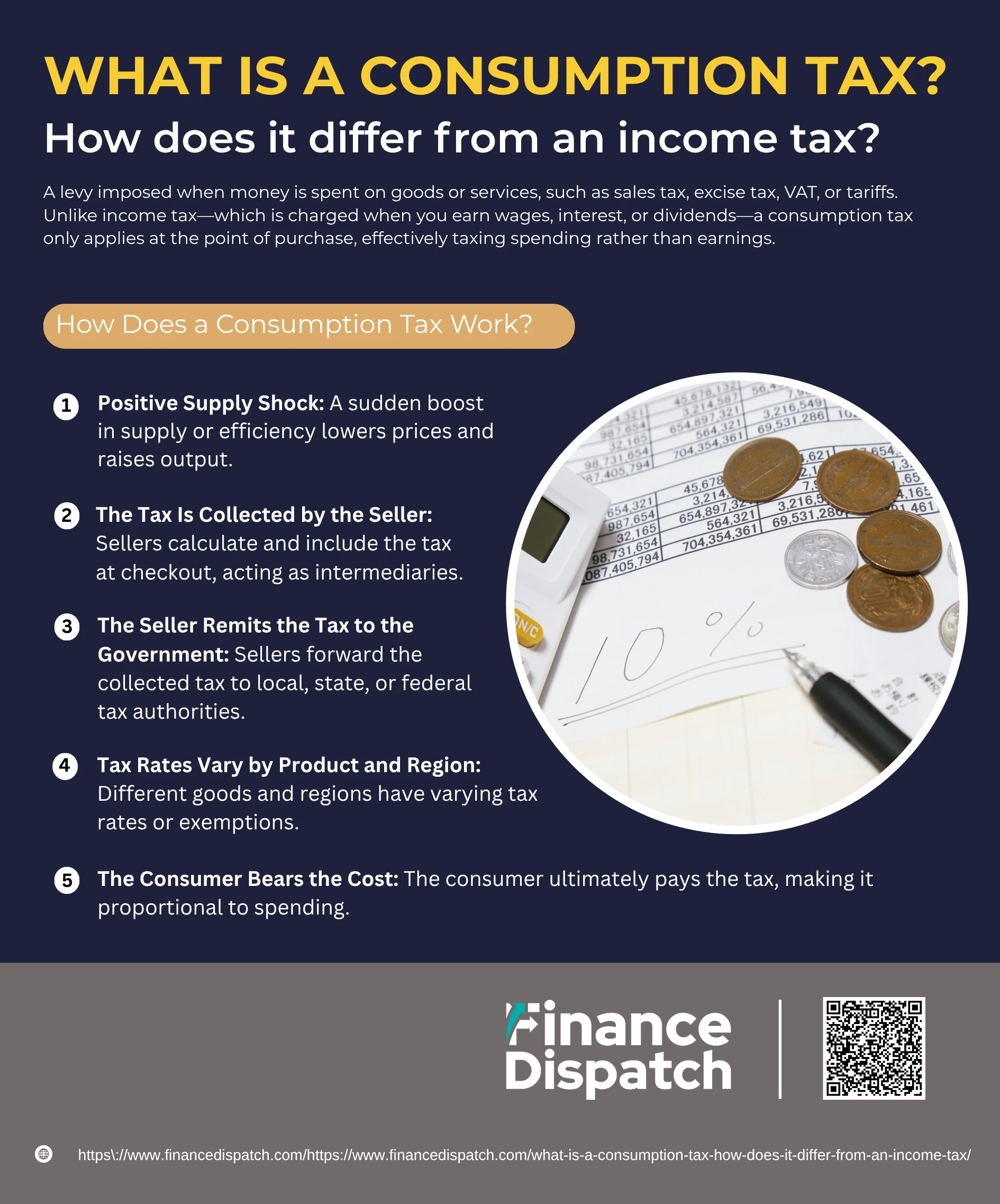

How Does a Consumption Tax Work?

How Does a Consumption Tax Work?

A consumption tax is applied when individuals or businesses spend money on goods or services, rather than when they earn it. This tax is typically embedded in the purchase price and collected at the point of sale. Unlike income tax, which is directly levied on your earnings, consumption tax targets your spending habits. Its primary function is to shift the tax burden from income to expenditure, and it serves as a significant revenue source for many governments around the world. Let’s take a closer look at how this tax system functions in practice.

1. A Product or Service Is Purchased

When a consumer buys a taxable item—such as clothing, electronics, gasoline, or a dining experience—a consumption tax is added to the purchase price. This can be clearly shown at the register (like sales tax in most U.S. states) or be embedded in the cost (like VAT in many European countries). The consumer may not always be aware of the tax breakdown, but it’s part of the total amount paid.

2. The Tax Is Collected by the Seller

At the point of sale, the seller calculates the applicable consumption tax based on the current tax rate and includes it in the final invoice. This responsibility lies with the vendor or service provider, who acts as an intermediary between the consumer and the tax authority. In some cases, businesses use specialized software or systems to ensure accurate calculation, especially when different rates apply to different products or jurisdictions.

3. The Seller Remits the Tax to the Government

After collecting the tax from consumers, the seller is required to submit the amount to the relevant tax authority—whether local, state, or federal—on a regular basis. This is typically done monthly, quarterly, or annually, depending on the business’s size and local regulations. Failure to remit taxes properly can lead to audits, penalties, or legal consequences for the business.

4. Tax Rates Vary by Product and Region

Consumption tax is not a one-size-fits-all rate. Essentials like unprepared food, children’s clothing, or medical supplies are often taxed at a lower rate or exempt altogether. In contrast, non-essential or luxury items such as jewelry, high-end electronics, or tobacco products may carry higher rates. Additionally, different states or countries set their own tax structures. For instance, some U.S. states have no sales tax, while others like California may have rates exceeding 7%, plus additional local levies.

5. The Consumer Bears the Cost

Although the tax is administered by the seller, it is ultimately the consumer who pays it. This means the more you spend, the more tax you pay—making consumption taxes effectively proportional to your expenditures. Unlike progressive income taxes, which increase with earnings, consumption taxes apply uniformly to spending, regardless of income level. This leads to ongoing debates about fairness, especially since lower-income individuals typically spend a larger portion of their income on taxable goods.

Common Types of Consumption Taxes

Common Types of Consumption Taxes

Consumption taxes come in various forms and are applied differently depending on the item, transaction, or jurisdiction. While all of them are based on the idea of taxing spending instead of income, each type serves a unique function and affects consumers in distinct ways. Understanding the different types of consumption taxes can help clarify how governments generate revenue and how these taxes impact your everyday purchases.

Here are the most common types of consumption taxes:

1. Sales Tax

Sales tax is a percentage-based tax applied at the point of sale on most retail goods and some services. It is one of the most familiar forms of consumption tax in the United States. While not imposed at the federal level, most U.S. states and many localities levy their own sales taxes, which are collected by the seller and remitted to the government. Some necessities like groceries or medicine may be exempt depending on the region.

2. Value-Added Tax (VAT)

A value-added tax is widely used in over 160 countries, including those in the European Union, Canada, and Japan. VAT is a multi-stage tax applied at each point in the supply chain—from raw materials to final sale—on the “value added” at each step. While it’s less visible to consumers than sales tax, it ultimately increases the cost of goods and services.

3. Excise Tax

An excise tax targets specific products or activities, such as alcohol, tobacco, gasoline, or gambling. These taxes are often included in the price of the product and are sometimes used to discourage consumption of certain goods. When applied for this purpose, they’re often referred to as “sin taxes.” Excise taxes can also fund specific programs, like road maintenance from gasoline taxes.

4. Import Duties (Tariffs)

Import duties are taxes levied on goods brought into a country from abroad. These taxes are usually paid by importers, who pass the added cost on to consumers through higher retail prices. The rate can vary depending on the item, country of origin, and trade agreements. Import duties can serve economic goals, such as protecting domestic industries.

5. Use Tax

Use tax is similar to sales tax but applies when you purchase goods from out-of-state sellers who don’t collect your local sales tax. It is the buyer’s responsibility to report and pay this tax to their home state. For example, if you buy a product online from a seller in a state with no sales tax and use it in your state that does have a tax, you may owe a use tax.

Examples of Consumption Taxes

Consumption taxes are embedded in many everyday transactions, whether you’re filling your gas tank, booking a flight, or shopping for clothes. While the specific rates and rules vary by country and region, these taxes are generally paid at the point of sale and are often hidden in the final price. Here are some common real-world examples that show how consumption taxes are applied in different situations:

1. Sales Tax on Electronics: When you buy a $1,000 laptop in California, you might pay an additional $72.50 in sales tax at a 7.25% state rate—excluding any additional city or county taxes.

2. Excise Tax on Gasoline: At the pump, the price per gallon already includes federal and state excise taxes used to fund road infrastructure and maintenance.

3. Value-Added Tax (VAT) on Clothing in Europe: In countries like Germany or France, the price tag for clothes includes a VAT—often around 20%—which is added at each stage of the supply chain.

4. Import Duty on Foreign Cars: If you import a luxury car into the U.S., you may pay a significant import duty based on the car’s value, weight, or type, which adds to the vehicle’s retail price.

5. Sin Taxes on Cigarettes and Alcohol: These products carry high excise taxes intended to both generate revenue and discourage unhealthy behaviors.

6. Use Tax on Out-of-State Purchases: If you buy furniture online from a seller that doesn’t charge your state’s sales tax, you’re typically required to report and pay a use tax when filing your state tax return.

Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax

Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax

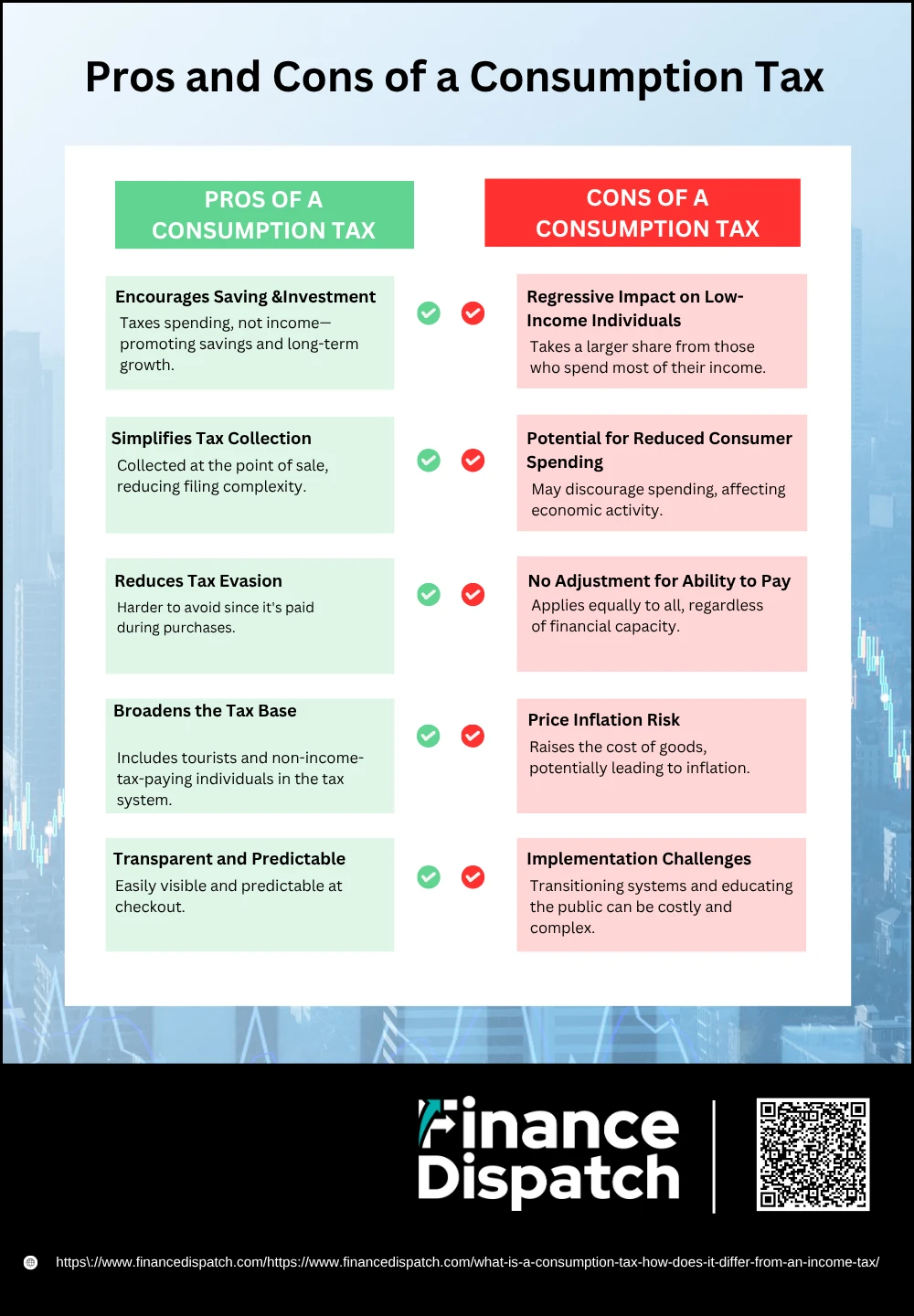

Consumption taxes—applied when you spend money rather than when you earn it—are used widely around the world. Advocates say they simplify the tax system, reward savings, and ensure broader participation in tax contributions. Opponents argue that they place a heavier burden on low-income households and may discourage essential spending. To better understand this system, it’s important to weigh both its advantages and disadvantages across economic, social, and administrative dimensions.

Pros of a Consumption Tax

1. Encourages Saving and Investment

Because the tax is only applied when money is spent, individuals are not penalized for earning or saving. This creates a financial incentive to save and invest, which can lead to more capital accumulation and long-term economic growth.

2. Simplifies Tax Collection

Consumption taxes are typically collected at the point of sale by businesses, making the process easier and more straightforward for tax authorities compared to income tax systems that require individual filings, complex deductions, and audits.

3. Reduces Tax Evasion

Unlike income taxes, which can be evaded through underreporting or exploitation of loopholes, consumption taxes are harder to avoid. Everyone who spends money pays the tax, making compliance nearly automatic.

4. Broadens the Tax Base

This tax applies to anyone making purchases, including tourists, temporary workers, and undocumented individuals who may not pay income tax. As a result, it generates revenue from a wider segment of the population.

5. Transparent and Predictable

Consumers can clearly see the tax added to the price at checkout or as part of the receipt. This visibility increases transparency and helps individuals better understand how much tax they are paying.

Cons of a Consumption Tax

1. Regressive Impact on Low-Income Individuals

Consumption taxes take a larger percentage of income from low-income individuals, who tend to spend most of what they earn. For example, a 10% tax on groceries affects a low-income earner far more than a wealthy person who spends a smaller share of their income on essentials.

2. Potential for Reduced Consumer Spending

Taxing purchases can discourage people from buying non-essential goods or even necessities. This reduction in spending can slow down economic activity, especially during economic downturns.

3. No Adjustment for Ability to Pay

Unlike progressive income tax systems where higher earners pay a greater percentage, consumption taxes apply the same rate to everyone, regardless of income or financial capacity, which can be perceived as unfair.

4. Price Inflation Risk

Since the tax is added to the cost of goods and services, it effectively raises prices. This can lead to inflationary pressure, making everyday goods more expensive—especially harmful when applied to necessities.

5. Implementation Challenges

Shifting from an income-based to a consumption-based system requires massive administrative, legal, and infrastructural changes. Educating the public and businesses about new rules, software, and compliance requirements can be costly and time-consuming.

Consumption Tax vs. Income Tax

Taxes are essential for funding government services, but how those taxes are levied makes a big difference in how people experience and respond to them. Two of the most commonly discussed forms are consumption tax, which is applied when you spend money, and income tax, which is applied when you earn it. Each tax type has its own structure, economic impact, and fairness implications. While some argue that consumption taxes promote savings and simplify compliance, others highlight the progressive nature of income taxes in balancing wealth distribution.

Here’s a side-by-side comparison to help clarify the key differences:

| Feature | Consumption Tax | Income Tax |

| Tax Trigger | Spending money on goods or services | Earning money from work, business, or investments |

| Form | Indirect tax (e.g., sales tax, VAT, excise) | Direct tax on wages, salaries, capital gains, etc. |

| Payment Point | At the time of purchase | Usually deducted from paycheck or filed annually |

| Collected By | Vendor/seller at point of sale | Government through payroll systems or annual filings |

| Progressiveness | Generally regressive—same rate for all, affects lower incomes more | Progressive—higher earners pay higher rates |

| Encourages | Saving and investing | Redistribution of wealth and funding of public services |

| Complexity | Simpler to administer | More complex, with deductions, brackets, and reporting |

| Compliance Burden | Low for individuals (handled by sellers) | High for individuals and businesses (filings, audits) |

| Example | 10% sales tax on a $100 item = $10 tax | 25% tax on $100,000 income = $25,000 tax |

| Used In | Common in EU, Japan, Canada (VAT systems) | Used widely in U.S. at the federal level |

Can You Deduct Consumption Taxes?

Whether or not you can deduct consumption taxes depends on your tax status and the type of tax involved. For individuals in the U.S., state and local sales taxes can be deducted on your federal income tax return if you choose to itemize deductions instead of taking the standard deduction. However, you must choose between deducting sales tax or state income tax—you can’t deduct both. This deduction may be particularly useful if you made large purchases during the year, such as a car or major home appliance. On the other hand, other types of consumption taxes like excise taxes, import duties, or hotel occupancy taxes generally aren’t deductible for personal expenses. For businesses, many consumption taxes—especially those paid on goods and services used in operations—are deductible as business expenses or can be included in the cost of goods sold.

Conclusion

Consumption taxes play a significant role in how governments raise revenue, offering an alternative to traditional income-based taxation. By taxing spending rather than earnings, these taxes aim to encourage saving and simplify the tax collection process. However, their regressive nature raises important concerns about fairness, especially for lower-income individuals who spend a larger portion of their income on taxable goods. Understanding the differences between consumption and income taxes—from how they work to their economic impact—can help individuals, businesses, and policymakers make more informed decisions about financial planning and tax reform.