Taxes are meant to be straightforward—citizens and businesses pay their fair share to fund public services. Yet hidden within the thousands of pages of tax codes are loopholes: legal gaps, ambiguities, or oversights that allow people to reduce what they owe without breaking the law. Unlike tax evasion, which is outright illegal, tax loopholes operate in a gray zone—completely lawful but often unintended by lawmakers. From multinational corporations shifting profits overseas to wealthy individuals leveraging clever financial strategies, loopholes have become a tool for minimizing tax burdens, sparking debates about fairness, legality, and ethics in modern taxation.

What is a Tax Loophole?

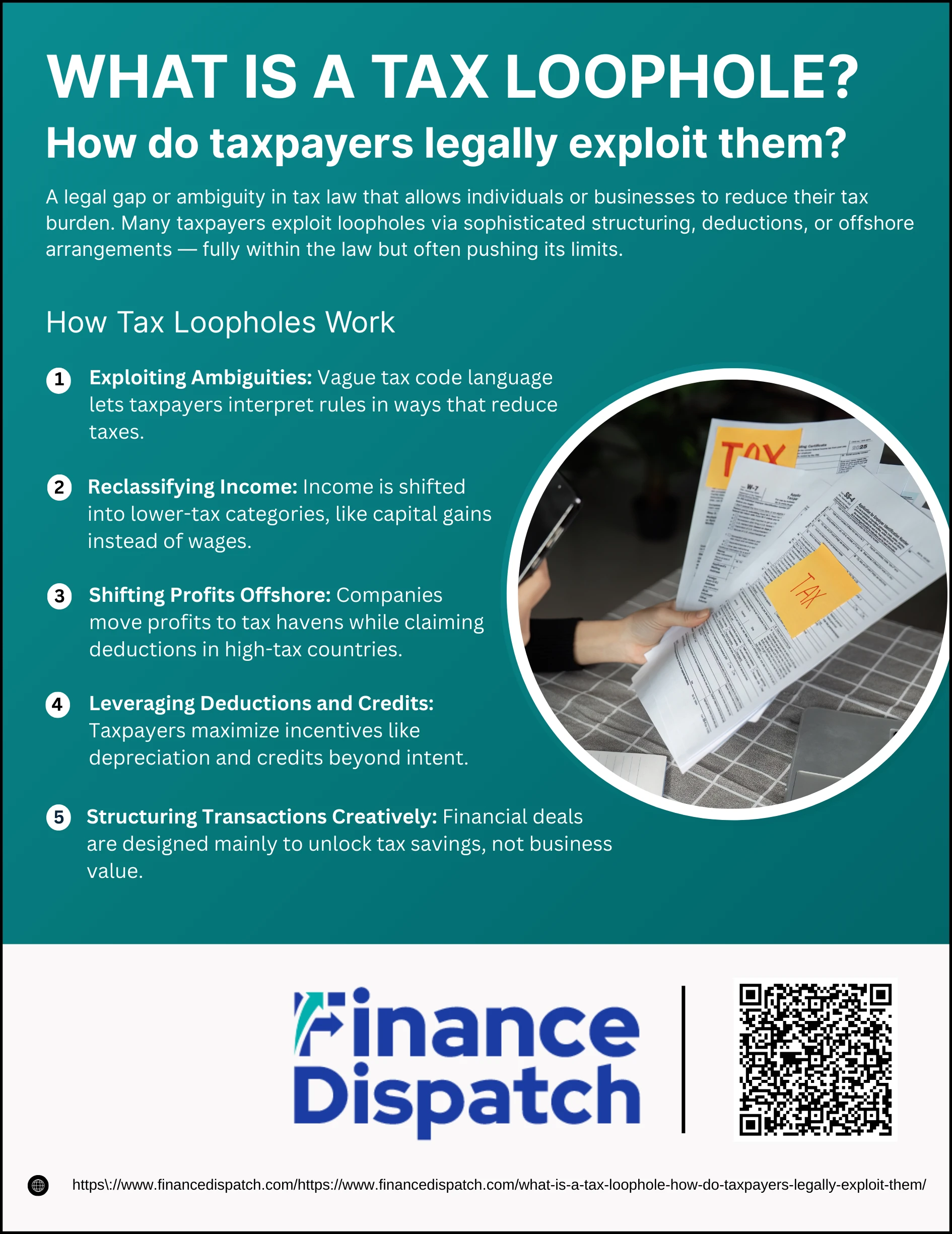

A tax loophole is a gap, ambiguity, or unintended provision in the tax code that allows individuals or businesses to reduce their tax liability without breaking the law. Unlike tax evasion, which involves illegal practices such as concealing income, loopholes rely on exploiting technicalities in legislation. They often arise from overly complex laws, vague definitions, or overlooked interactions between different rules. While some loopholes are deliberately created as incentives—for example, to encourage investment in certain industries—many are accidental, discovered only when savvy taxpayers or their advisors find ways to navigate around the original intent of lawmakers.

How Tax Loopholes Work

How Tax Loopholes Work

Tax loopholes operate by taking advantage of gaps or quirks in the tax code. While they are fully legal, they often allow taxpayers to achieve results lawmakers never intended—like reducing taxable income, moving profits overseas, or reclassifying earnings. Below are some of the main ways loopholes work in practice:

1. Exploiting Ambiguities

Tax codes are filled with technical language and complicated definitions. When these definitions are vague, taxpayers and their advisors interpret them in ways that reduce taxes. For instance, a law meant to support investment in renewable energy might be applied broadly to other unrelated activities, creating an unintended tax break.

2. Reclassifying Income

Income can be categorized in different ways, and the tax rate applied varies depending on the category. A common example is the carried interest loophole, where hedge fund managers classify their compensation as long-term capital gains (taxed at a lower rate) instead of ordinary income. This simple reclassification can save millions in taxes.

3. Shifting Profits Offshore

Multinational corporations often move profits to subsidiaries in low-tax countries like Bermuda or Luxembourg. At the same time, they shift debt and expenses to high-tax jurisdictions, which allows them to claim deductions. This “profit shifting” ensures they appear less profitable in high-tax nations while keeping more earnings shielded abroad.

4. Leveraging Deductions and Credits

Deductions and credits are meant to encourage beneficial behaviors—like buying a home, investing in education, or supporting clean energy. However, wealthy taxpayers and corporations often structure their finances to maximize these incentives far beyond what lawmakers envisioned. Real estate investors, for example, use depreciation rules to continually reduce taxable income even when their property values rise.

5. Structuring Transactions Creatively

Some tax loopholes are unlocked by designing financial transactions specifically for tax purposes rather than for genuine business needs. This can include creating shell companies, using trusts to pass wealth to heirs, or designing “paper losses” that offset taxable income. While the business logic may be thin, the tax savings can be substantial.

Common Examples of Tax Loopholes

Tax loopholes come in many forms, from clever financial strategies to complex corporate arrangements. While some are intentional incentives created by lawmakers, others are unintended side effects of tax legislation. Below are some of the most common examples that taxpayers and corporations legally use to lower their tax bills.

1. Carried Interest Loophole: Allows hedge fund and private equity managers to classify their earnings as capital gains, taxed at lower rates than regular income.

2. Backdoor Roth IRA: Enables high-income earners to bypass income limits and contribute to Roth IRAs by converting funds from traditional IRAs.

3. Offshore Tax Havens: Multinational corporations shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions (like Bermuda or Luxembourg) while claiming deductions in high-tax countries.

4. Depreciation Deductions: Real estate investors reduce taxable income by writing off property value over time, even when property values increase.

5. Step-Up in Basis for Inheritance: Heirs avoid capital gains taxes by resetting the value of inherited assets to their market price at the time of inheritance.

6. The Augusta Strategy: Business owners rent their personal residence to their own company for meetings, claiming the expense as a business deduction while avoiding tax on the rental income.

7. Opportunity Zone Investments: Investors defer or reduce capital gains taxes by reinvesting profits into government-designated distressed areas.

How do taxpayers Legally Exploit Loopholes

Taxpayers exploit loopholes by carefully structuring their finances to fit within the gaps or exceptions in tax law. These strategies are not illegal—unlike tax evasion—but they often achieve outcomes lawmakers never intended, such as lowering taxable income or shifting profits to friendlier jurisdictions. Both individuals and corporations rely on financial advisors, accountants, and legal experts to identify and maximize these opportunities.

Table: Common Ways Taxpayers Legally Exploit Loopholes

| Method | How It Works | Typical Beneficiaries | Why It Matters |

| Reclassifying Income | Shifting wages into lower-tax categories like capital gains | Hedge fund & private equity managers | Saves millions by lowering tax rate from ordinary income levels |

| Profit Shifting Offshore | Moving profits to subsidiaries in tax havens while claiming expenses in high-tax countries | Multinational corporations | Reduces taxes in home country; deprives governments of revenue |

| Retirement Account Loopholes | Using “backdoor” Roth IRAs to bypass income limits on contributions | High-income individuals | Allows tax-free growth of retirement funds, even for those above legal thresholds |

| Depreciation Rules | Writing off property value over time, even if property gains value | Real estate investors | Creates paper losses that reduce taxable income |

| Augusta Strategy | Renting personal residence to one’s business tax-free (up to 14 days annually) | Small business owners | Converts personal expenses into deductible business costs |

| Step-Up in Basis | Resetting inherited asset value at time of death to avoid capital gains taxes | Wealthy families & heirs | Allows inherited wealth to pass with minimal or no capital gains tax liability |

Tax Loopholes for Real Estate & Small Businesses

Tax Loopholes for Real Estate & Small Businesses

Real estate and small businesses often benefit from tax provisions that reduce taxable income, delay payments, or create favorable tax treatment. While these strategies are legal, they highlight how much more flexibility larger investors and entrepreneurs can enjoy compared to the average taxpayer. Below are the most common loopholes, explained in detail:

1. 1031 Exchange (Like-Kind Exchange)

This provision lets investors sell an investment property and reinvest the proceeds into another property of equal or greater value without immediately paying capital gains tax. Instead, the tax is deferred until the final property is sold without reinvestment. Many investors keep rolling over properties, delaying taxes for decades, and in some cases, passing the property to heirs who benefit from a “step-up in basis,” avoiding taxes altogether.

2. Depreciation Deductions

The tax code allows property owners to write off the gradual “wear and tear” of their buildings, even if the property is increasing in market value. For example, a residential property can be depreciated over 27.5 years. Real estate investors often use cost segregation studies to accelerate depreciation on parts like fixtures or carpeting, maximizing deductions in early years. These deductions often create paper losses that offset rental income, reducing taxable income significantly.

3. Opportunity Zone Investments

Created under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, this incentive encourages investment in economically distressed areas. Investors who reinvest capital gains into a Qualified Opportunity Fund can defer paying taxes until 2026 (or until they sell the investment). If they hold the investment for 10 years or more, any appreciation becomes tax-free. This allows wealthy investors to both save on taxes and build long-term portfolios while claiming they are supporting community development.

4. Self-Directed IRAs

Unlike traditional retirement accounts that limit you to stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, a self-directed IRA allows investments in real estate, private businesses, or even precious metals. With a traditional self-directed IRA, earnings are tax-deferred until withdrawal; with a Roth version, withdrawals in retirement are tax-free. Business owners and investors use this to grow wealth in tax-advantaged accounts far beyond typical retirement contributions.

5. Home Office and Business Expense Deductions

Small business owners can deduct legitimate business expenses from their taxable income. This includes part of their rent or mortgage if they maintain a home office, mileage for business driving, meals tied to client meetings, or even portions of travel when combined with business activity. These deductions can significantly lower taxable profits, something regular employees can’t typically do.

6. The Augusta Strategy

Named after Augusta, Georgia, where homeowners rent their houses to companies during the Masters golf tournament, this strategy allows a homeowner to rent out their residence to their own business for up to 14 days a year. The business deducts the rental expense, and the homeowner pays no tax on the rental income, provided the arrangement is properly documented. It’s a powerful way for small business owners to move money out of their business tax-free.

7. Qualified Business Income (QBI) Deduction

This deduction, introduced in 2018, allows owners of pass-through businesses (sole proprietorships, partnerships, LLCs, and S-Corps) to deduct up to 20% of their qualified business income. For instance, if a business nets $100,000 in income, only $80,000 may be taxable after the QBI deduction. While there are income limits and restrictions on certain service industries, strategic structuring often allows businesses to qualify.

Economic and Social Costs of Loopholes

While tax loopholes offer savings for those who use them, they also create hidden costs for society at large. Governments lose valuable revenue, public trust in the tax system weakens, and economic fairness is undermined. Over time, these effects ripple through society—reducing funding for services, widening inequality, and distorting business behavior.

Key Costs of Tax Loopholes:

1. Revenue Losses for Governments – Billions in potential tax dollars are lost each year, limiting funds for healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

2. Widening Inequality – Wealthy individuals and corporations benefit most, shifting the tax burden onto middle- and lower-income taxpayers.

3. Distorted Economic Incentives – Loopholes encourage tax-driven decisions, like excessive stock-based compensation or offshore profit shifting, instead of productive investment.

4. Added Complexity – A loophole-ridden tax system forces individuals and businesses to spend more on accountants, lawyers, and compliance costs.

5. Erosion of Public Trust – When people see the rich avoiding taxes legally, it fuels cynicism and reduces voluntary tax compliance.

Closing the Loopholes: Reforms and Challenges

Governments worldwide recognize that tax loopholes drain revenue and undermine fairness. Yet closing them is rarely simple. Loopholes often arise from complex legislation, and powerful interests lobby hard to keep them open. Even when reforms succeed, new gaps quickly emerge. Effective solutions require a balance between simplifying tax laws, enforcing compliance, and maintaining incentives for investment.

Key Approaches to Closing Loopholes:

1. Review and Revise Tax Laws – Conduct regular audits of tax codes to identify unintended gaps and amend or repeal problematic provisions.

2. Introduce General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) – Give tax authorities power to disregard transactions designed primarily for avoidance purposes.

3. Strengthen International Cooperation – Address cross-border avoidance through initiatives like the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project.

4. Simplify the Tax Code – Reduce complexity by limiting exemptions, deductions, and special provisions that create loophole opportunities.

5. Increase Enforcement and Penalties – Use audits, fines, and stricter reporting requirements to discourage aggressive loophole exploitation.

6. Enhance Transparency – Require clearer disclosure of tax strategies (such as through Disclosure of Tax Avoidance Schemes, DOTAS) to detect abuse earlier.

Conclusion

Tax loopholes reveal the tension at the heart of modern taxation: the difference between what is legal and what feels fair. While they allow individuals and corporations to reduce their tax burdens within the boundaries of the law, the broader economic and social costs—lost revenue, rising inequality, and eroded trust—are harder to ignore. Closing loopholes is never straightforward; every fix risks creating new gaps, and political resistance often slows reform. Ultimately, the challenge lies in striking a balance: designing a tax system that encourages growth and investment while ensuring that all taxpayers, regardless of wealth or influence, contribute their fair share to the societies they benefit from.